Abstract

Code-switching (e.g., “Are you hungry? Est-ce que tu veux une apple?”) is common in bilingual environments and may affect language acquisition. For example, code-switching has been shown to slow toddlers’ language processing, especially when it occurs within a syntactic phrase (Byers-Heinlein et al., 2017; Potter et al., 2018). In everyday life, the impact of code-switching on language acquisition likely depends on the frequency and syntactic location of the code-switching children typically hear. Some bilingual children hear code-switching frequently, as indicated by parental-reports (Byers-Heinlein, 2013) and short laboratory studies (Bail et al., 2015), although these studies are limited by possible reporting biases and observer effects. We examined parents’ natural code-switching behaviors in a corpus of infants’ language environments, recorded using Language ENvironment Analysis (LENA) devices, and addressed three questions regarding the frequency and syntactic location of parental code-switching.

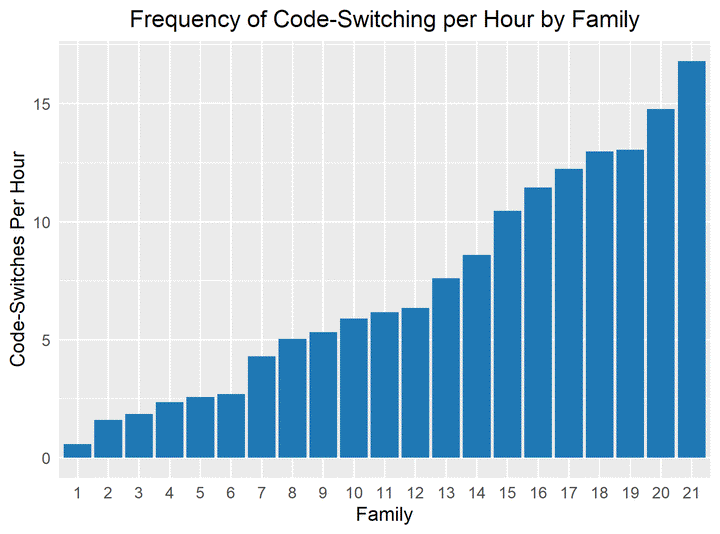

Method. Twenty-one French-English bilingual families in Montréal contributed three full-day recordings when their infant was 10-months-old, and 16 of these families contributed an additional day when their infant was 18-months-old. Montréal is a unique bilingual environment, as French and English have high status and are prevalent in the larger community, which may lead to different code-switching behaviors than those observed in other communities. We defined code-switching as any language change by a single speaker. Research assistants identified instances of code-switching and their syntactic location (between sentences, within sentence at a phrase boundary, within sentence not at a phrase boundary). Here, we report preliminary data from 120 hours of recordings provided by 5 families.

Q1: How often do parents code-switch? We found code-switching to be surprisingly rare, occurring on average 7 times per hour (sd = 5, min = 1, max = 12), contrasting with data showing that Spanish-English parents code-switched 25 times in only 13 minutes (Bail et al., 2015).

Q2: Are code-switches more frequent within or between sentences? Parents code-switched more often between sentences (72%) than within a sentence (28%). However, we observed large variation between families, ranging from 53% to 100% of code-switches occurring between sentences.

Q3: Do within-sentence code-switches occur at syntactic phrase boundaries? Parents switched slightly more often at a phrase boundary (62%) than within a phrase (38%). Again, we saw large family-to-family variation, ranging from 25% to 90% of within-sentence switches occurring at phrase boundaries.

Conclusion. These results show that a) code-switching was relatively rare in our corpus, b) switches were produced in a variety of syntactic locations both between and within sentences, and c) family-to-family variation was large. Together, these and previous results (Byers-Heinlein, 2013 Bail et al., 2015) suggest code-switching frequency and syntactic location vary substantially from family to family and community to community. Therefore, each bilingual child may face unique challenges in language acquisition. The variation between communities and families could stem from different motivations for code-switching (e.g., teaching vocabulary, adding emphasis, conventionalized switches), and speaker characteristics (e.g., language dominance), questions we plan to explore. We will also investigate code-switching by speaker, and how parental code-switching changes between 10- and 18-months of age.