Rhythmic Similarity and Advantages on Vowel Perception: Differences among 9-month-old Dutch bilinguals (Poster)

Abstract

In order to successfully acquire both of their languages, bilingual children must discriminate the two languages in their environment. Rhythmicity appears to be a linguistic cue that bilingual infants quickly adopt to differentiate their native languages since birth (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2001; Byers-Heinlein, Burns, & Werker, 2010). Rhythm may mark input as belonging to one language or the other, and could potentially aid further steps in language acquisition, such as learning the phonemic contrasts specific to their languages (Curtin, Byers-Heinlein, & Werker, 2011; Havy, Bouchon, & Nazzi, 2016; Sundara & Scutellaro, 2011). The development of bilinguals’ phonemic discrimination abilities has not been found to follow one cohesive developmental timeline (c.f. Albareda-Castellot, Pons, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2011; Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2003; Liu & Kager, 2015; Sundara, Polka, & Molnar, 2008).

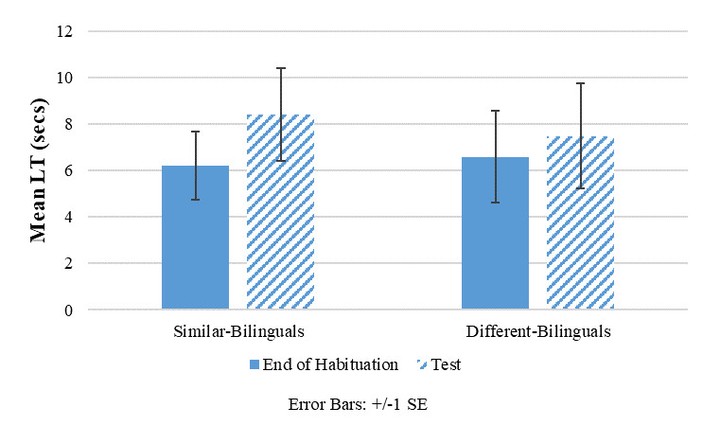

The current study builds upon these discrepancies by evaluating phoneme discrimination in light of the similarity, or dissimilarity, of the rhythmic properties of a bilingual’s languages. It is unclear from previous studies if rhythmic similarity (Havy, Bouchon, & Nazzi, 2016) or dissimilarity (Sundara & Scutellaro, 2011) bolsters bilinguals’ discrimination abilities. The current study directly compares two groups of 8-9 month-old bilinguals (one group whose languages are rhythmically similar, the other rhythmically dissimilar) on a native vowel contrast. /n/ In total, 29 Dutch bilingual infants were tested on the native /i/ - /ɪ/ vowel contrast via a visual habituation paradigm. Participants were first habituated over multiple trials to one of the vowels, as measured by looking time (LT). A trial ended if the infant looked away for more than 2 consecutive seconds, or the trial reached the maximum duration of 45 seconds. Once the habituation criteria was reached, they heard two trials of the other vowel in the test phase. Discrimination of the vowels was indicated by a significant recovery of LT between the mean of the last two trials in the habituation phase and the mean of the two trials in the test phase.

As a single group, 8-9 month-old Dutch bilingual infants were found to discriminate the native vowel contrast, t(28) = -2.349, p = .013. The sample was further divided based on the languages the participants were learning. The results showed that those learning two rhythmically similar languages discriminated the contrast, t(17) = -3.120, p = .003, whereas those learning two rhythmically dissimilar languages did not, t(10) = -.586, p = .286 (see figure above).

The results from this study suggest that at 8-9 months, bilinguals learning two rhythmically similar languages were able to discriminate the contrast, but bilinguals learning two rhythmically different languages were not. These results are consistent with those of Havy and colleagues (2016), but must be interpreted with caution, since it is possible that cross-linguistic transfer influences this difference between groups.